Show 22

Changes

Felix Schramm

February 16 - May 16, 2018

Theses on Sculpture

I once called Felix Schramm’s work—still in progress on that previous occasion—a “showcase of incoherence.” This stemmed from having observed that his work, while indebted to the sculptural in terms of provenance, wasn’t prepared to accept “sculpture” as a conceptual guarantee or the material embodiment of media exclusivity. This time, I would go so far as to grasp Schramm’s entire approach in general via the terms “showcase” and “incoherence,” albeit without ever dropping the connection to “sculpture.” In fact, this specific approach seems to me to be one of the few approaches in the field of sculpture with any remaining artistically productive potential (or, dogmatically speaking, one of the few approaches possible at all in that field). Schramm doesn’t entrench himself in traditionalism (as if sculpture could just carry on eternally as an “art medium” independent of history like painting or photography) or the typical authenticism of plastic arts. Nor does he so neatly sidestep the absolutely interesting “problem medium” under situational pressure (such as by veering off into some rhetoric notoriously waved through as progressive—collage, installation, process art).

That makes me all the more for looking at Schramm’s works precisely as sculptures. Sculptures that willfully present showcases of incoherence—and in so doing, disregard the traditional standards of plastic success while refraining from any opportunistic recourse to a hip format or a more easily consumable order. If nothing else, that helps me resolve my own issue: I’d much rather look at the synergy between image, thing, and art with images than in things outfitted with the claim of being art and having to take the claim over the thing for lack of alternative. (No doubt there are more than plenty such things, just rarely interesting.)

A real complex of works would evolve out of that particular piece Schramm was working on before—since 2012, the Accumulations have constituted the center of gravity within a body of work steadily expanding in content and display scheme.

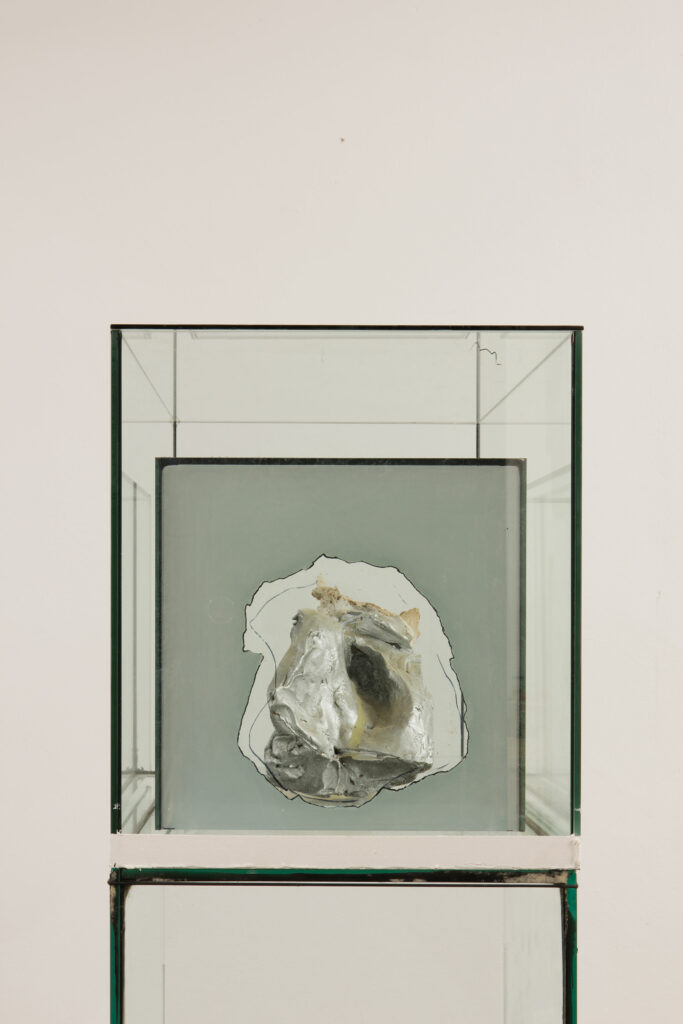

The distinctive feature of Schramm’s Accumulations is exactly what makes them literal showcases. They’re structured around vitrines, the majority of which constructed by the artist himself, sometimes found or commissioned: Containers made of glass or plexiglass operating as both display case and display. Which may be multi-tiered or grouped into different divisions, sometimes attached together additively, perhaps nested one inside the other. Schramm’s vitrines serve—functionally speaking—both storage and presentation. In doing so, they make a proper show of showing or presenting. These cases contain various things—outright heterogeneous elements in fact, and it’s not always easy to determine at first glance what the deal is with them. Some contents are evidently “planned,” “designed,” and “shaped,” e.g. miniature models of sweeping sculptural propositions of architectonic proportions such as have become a Schramm trademark since the turn of the millennium. Then some objects look like stand-alone statuettes apparently made from molds or casts of body parts with accurate human proportions. These, too, refer back to another group of Schramm’s works. Other things look “found,” in “reserve”: fragments, scraps, or plain old materials which—for whatever reason—got saved and deemed worthy of showing.

The glass cases certainly give all those diverse accumulated components a unifying formal element. Yet, scales and proportions clash inside, specimen and genre collide, as do model and product. As if that weren’t enough, exhibit and display, showpiece and mode of presentation collapse together. The Accumulations inhabit unstable semiotic terrain. Even that which looks like plastic object matter (blank material, scrap, found object) appears to have been at the very least manipulated, trimmed for a certain effect—not without evoking the argument between Arte Povera artists Jannis Kounellis and Pino Pascali over material honesty and truth to materials. The latter artist opted for an ambiguous use of material and so for the particular space then taken up by the sculpture, as in “Le Armi” (1965), a hyperrealistic series of weaponry made of cardboard, wood, and metal pieces, or his later nature reconstructions (1968). No question which side Felix Schramm would take.

For their part heterogeneous, the Accumulations ask to be discovered bit by bit, to be seen in and of themselves. The mode of presentation is equally suggestive of order, yet without underpinning any connections. More the contrary. Although visibly constructed according to a plan and artfully so, there is no privileged viewing position, no central perspective angle, and no ideal tracking shot. That would definitely explain the construction plans, and with that the structures, possibly even the point of these objects, too. Objects whose format hardly exceeds the dimensions of a small piece of furniture. And you have to treat an Accumulation like a piece of furniture—let’s take a Baroque secretary for example, or why not a collector’s vitrine. Being a sculpture, the Accumulation obviously demands to be circled, discovered successively; forces the viewer to bend or stretch; entices you to touch with a calculated opening here; withdraws there—one of the most efficient techniques of seduction. No Accumulation will ever be fully transparent, you’ll never get one fully under control. Anyway, they’ll always have multiple parallel sides that may absolutely contradict each other. And you’ll miss the best part too often, of course.

That the whole and its parts must be in some way cohesive is clear. Consistency in Schramm’s work derives from a plan of another order. This plan is founded upon incoherence, a principle which governs the single components no differently than the whole Accumulation. That includes breaks and insertions in terms of dimensions or placement of mismatched content. However, to paraphrase Helmut Draxler, basically no cohesive constellation can get by without coercion. That might be the lesson the Accumulations assign us. Beyond that, they’re inventory and repositories for different conceptual possibilities and technical states of sculpture, realized or not. The Accumulations interlock aspects of model, sculpture, and stage.

From that vantage point, it’s interesting to look back on the artist’s project as a whole. Felix Schramm’s body of work appears to be organized by an aesthetics of incoherence. Breaks, insertions, content mismatched in dimensions or order—that all characterizes his sweeping propositions as well, which are developed on-site, for the site not only in keeping with their own conceptual logic. It would be misleading to interpret them as site-specific operations or even in the sense of an intervention, even if these pieces and their partly monumental proportions do at times block the way in magnificently dysfunctional style. Interpreted from that point of view, they would have to be lacking criticality—that precisely targeted institutional-critical impulse—ultimately just pretending to challenge institutional space concretely by challenging architectonic space. Alongside the exhaustive conceptualization of art since the 1960’s, an anti-aesthetic attitude has taken hold that threatens to confuse the actual possibilities of art with its real—social or societal—effects. For Schramm, referencing the architectonic/institutional environment is hardly anything more than a production necessity, and he responds to that necessity in the spirit of a downright Baroque aesthetic: Real space shrinks to a model scenario by interplay with the wreckage sculptures confined within/breaking out. Because of their form qua size and fabrication with the technical arsenal of set construction, the dynamics get inverted with these pieces—yet, they stick within the givens of sculpture and, accordingly, stand there as theses.

It is only consistent for Schramm to currently use incoherence all the more on the “exhibition” constellation.

Hans-Jürgen Hafner