Archive Kienzle & Gmeiner Gallery (1997-2010)

Die Verfassung der Bilder

Elmar Zimmermann

August 13 - September 10, 2005

“Where is the central point, axis, pole, dominant interest, fixed position, absolute structure, or decided goal?

The mind is always being hurled towards the outer edge into intractable trajectories that lead to vertigo.”

—Robert Smithson, “A Museum of Language in the Vicinity of Art,” 1968

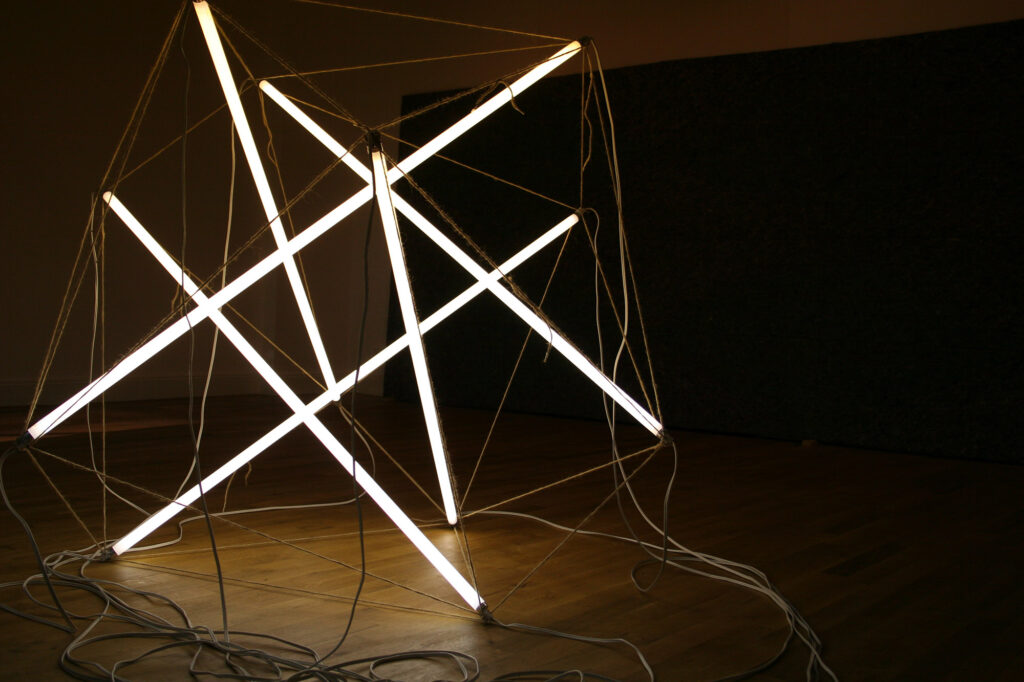

First the materials. A wide variety of qualities meet, substances of remote provenance seem to collide with the banal, the quotidian, such as worn-out roof lath or neon tubes. The works of Elmar Zimmermann, though always precisely defined in form and look (and also anchored as an installation through their place in the space), exhibit ruptures and seams. They take all the elements of which they are composed—which can mean that they take on states that seem arranged, sometimes even clearly constructed—and hold them together, floating in space.

What at first sounds like the lines of tradition, like the stories of the ready-made or the objet trouvé, or perhaps evokes an all too well known formula for beauty that was employed again by the Surrealists—now: Zimmermann certainly counts very precisely on his store of found pieces having its own life. (It contains model ships clearly made by hand that he recovered from the street, a dollhouse, or the upper part of an incubator, which Elmar includes in his decisions with a great deal of respect for the thing in itself. Other things, as diverse as the painting rags of colleagues or a worn-out parasol, are used more as ad lib resources, recognized as raw material, and then reformed in a goal-oriented, decisive process of transformation into a signetlike easel painting, for example, in which arte povere picking apart and sewing together with unpainterly, raw “house painting” avoid the merely tinkering by a hair’s breadth and produce the result “painting,” at the point which it may even be art.)

When one tries to talk about the cursed attractiveness of Zimmermann’s works, in addition to the obvious aspect of “material” another point, in some ways related to it, becomes important. For his materials have, of course, each incorporated their own stories. Stories that can only be rudimentarily deciphered, as soon as their functions are no longer clearly identifiable or the conditions of their original use simply no longer deducible. Then the story becomes surface, a kind of patina that Elmar Zimmermann’s works always include, only sometimes permitted, but sometimes out and out dramatized. But always with a homogenizing effect.

And that effect is what holds together the heterogeneous and disparate, the floating states and fractures in the paintings and objects, the frayed installation settings for more rapid perception for a time, before once again questions ignite and a need for clarification arises. For knowing the components and nature of these works is by no means enough to reveal what they are.

Let’s leave it as mere suggestions. Elmar Zimmermann is a retro Futurist and mineralogist, as an artist metallic glass seems just as self-evident as the “question whether it is a particle or a wave”—in keeping with the titles of a multipart installation that accumulates the rusting color field and warming light around an elegantly distorted, partially reflective geometry—as if in the wake of archaeological researches in around three hundred years (from today) a Buckminster-Fuller-like experiment with the sorry remnants of a chicken farm were to be recreated from a (supposed) recipe from Robert Smithson’s Collected Writings. And from that one had to conclude what the construction of art might have meant in the early twenty-first century…

In conclusion, what would it look like with the “constitution of images,” the art of society? Why are you asking me?

Hans-Jürgen Hafner © July 2005